These complex takeover vehicles serve an important purpose that’s worth protecting.

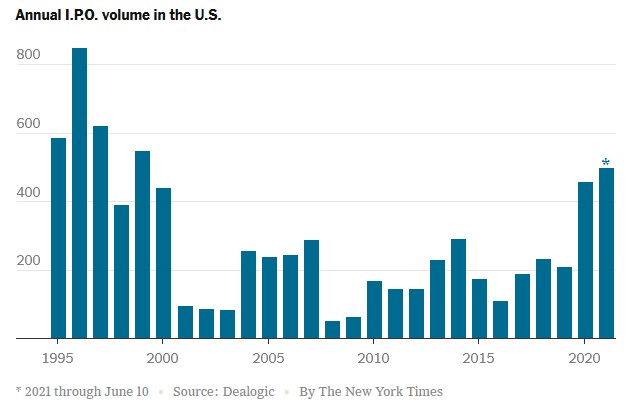

Special purpose acquisition companies, better known as SPACs, have single-handedly revived the market for initial public offerings, taking small companies public by the dozens. So far this year, there have been roughly twice as many listings of these blank-check companies as traditional offerings.

And since these cash shells — which raise money in an I.P.O. on the promise of merging with a private company within a couple of years, taking it public — often target emerging tech companies, that market has returned to its glory years.

Why, then, are regulators trying to kill it?

The assault has been quick and focused. First, the Securities and Exchange Commission’s head of corporate finance said the merger of a SPAC and its target company should be considered the “real I.P.O.,” which would remove the safe-harbor protections that SPACS have for forward-looking statements. That means SPAC mergers wouldn’t come with financial forecasts or other projections, a key difference from traditional I.P.O.s.

Next, S.E.C. officials issued a bulletin calling into question the accounting treatment of warrants, which they said should be considered liabilities instead of equity. This could delay the I.P.O.s and mergers of a significant number of SPACs as they alter their accounts.

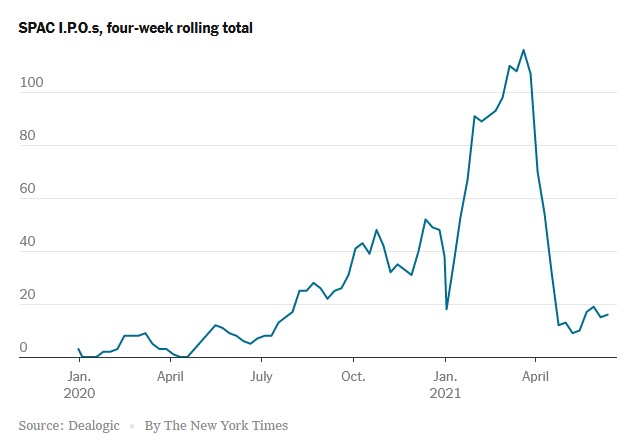

The effect of these announcements, both in April, is easy to see in the numbers.

The regulatory scrutiny of SPACs has been triggered by hand-wringing over whether they are too risky for retail investors, a question recently posed by Gary Gensler, the S.E.C. chairman.

Heck, back in 2008 I was writing about the perils of SPACs and their role in that year’s merger boom (which ended badly). While some companies that recently went public via a SPAC have been big successes, like the betting group DraftKings, others have flamed out, like the electric-truck maker Lordstown Motors, which said this week that it might not have enough cash to survive.

And with more than $130 billion in cash sitting in SPACs now looking for takeover targets, the competition for deals will no doubt drive up acquisition prices, making it harder to generate returns for investors, especially later ones.

But all of this misses the point. The SPAC, which has been around for decades, has brought back the I.P.O. market for innovative, smaller companies. Despite the recent slowdown, there have been more than 330 SPAC I.P.O.s this year, raising just over $100 billion.

Flash back to the late 1990s. The so-called Four Horsemen boutique banks — Alex. Brown, Hambrecht & Quist, Robertson Stephens and Montgomery Securities — cumulatively underwrote about 130 I.P.O.s a year at the time. It was a market where brokers could push smaller stocks to investors (think “Boiler Room”).

After the dot-com bubble burst and the Sarbanes-Oxley Act ushered in reforms to reduce broker conflicts, the small I.P.O. all but disappeared, the subject of a study of mine. Since then, there has been a much slower pace of I.P.O.s, almost all bigger companies.

Eventually, the notion that regulation had become too strict gained prominence, which led to the JOBS Act of 2012. This made it easier to go public, but the goal of giving public investors earlier access to innovative start-ups has proved elusive.

Enter SPACs, which are bringing many smaller companies to market. SPACs have found a way to raise ready capital via an I.P.O., long before approaching a company to acquire and transferring the funds. And there is also often additional investment from outside investors at the time of merger, which helps validate the deals.

Hedge funds are drawn to the post-I.P.O., pre-acquisition stage of SPACs because they earn interest on the amount they invest, receive warrants to capture more upside by buying more stock once the company merges with a target and can redeem their stock at the I.P.O. price if they don’t like the acquisition.

This is a decent investment. Where SPACs can run into trouble is during their second stage: when they make an acquisition. However, there is the aforementioned option to redeem stock at the time of the acquisition if shareholders don’t like it. A bigger problem is if shareholders who invest in SPACs after acquisitions are getting a particularly bad deal, which some research suggests.

Are they? SPACs are bringing riskier companies to market. Stock Market 101 suggests that with more risk come more reward and more failures.

Should investors be exposed to these sorts of companies, which are inherently riskier? Make your own judgment, but it wasn’t long ago when people were worried about start-ups staying private for too long, depriving public investors of exposure to potential gains. Now that the SPAC solves this problem, regulators are backpedaling.

And just as many people get familiar with SPACs, they are changing. Bill Ackman’s recent deal with Universal Music Group is complicated, to say the least, and the hedge fund manager’s SPAC will spawn a new spin on SPACs, which he calls a SPARC (special purpose acquisition rights company). This addresses some shortcomings of how SPACs work now, removing a time limit on finding a takeover target and not tying up investors’ funds before a deal is done. By my count, it’s the third generation of the SPAC’s evolution.

More disclosure should be required about the compensation that SPAC sponsors receive. And some SPACs are too aggressive or make companies public too soon or with faulty (or even fraudulent) business plans. But the same can happen with traditional I.P.O.s. That is not a reason to kill the only thing that has revived the market for I.P.O.s of small and emerging growth companies in 20 years.

Steven Davidoff Solomon, a.k.a. the Deal Professor, is a professor at the School of Law at the University of California, Berkeley, and the faculty co-director at the Berkeley Center for Law, Business and the Economy.